About Intestinal Worms

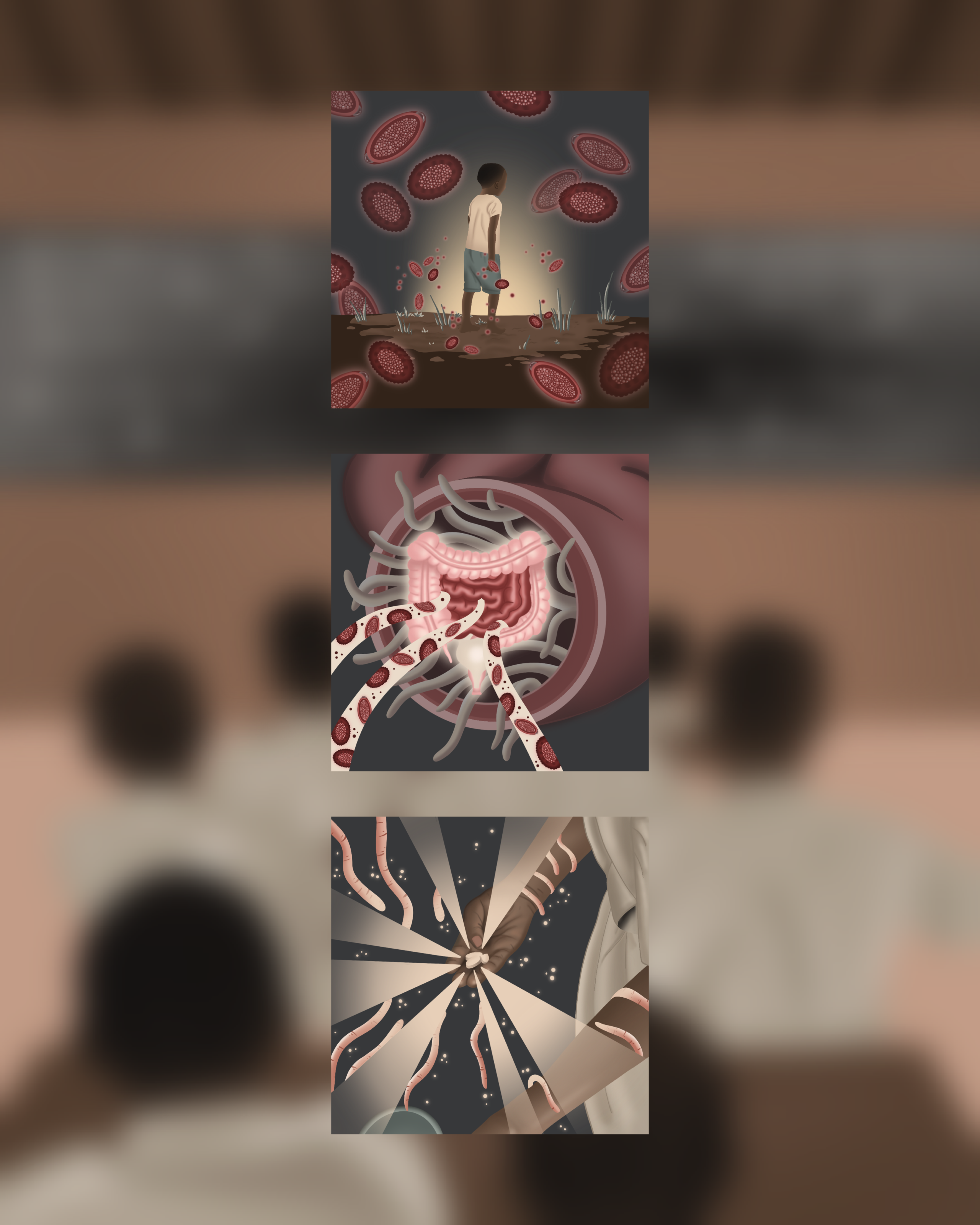

Nearly one billion children require annual treatment for intestinal worms, also known as soil-transmitted helminths. These parasitic infections cause malnutrition, anemia, and poor physical and mental growth.

Overview

Seven Things to Know about intestinal worms

(1) Intestinal worms are a group of parasites – hookworm, ascaris (roundworm), and trichuris (whipworm) – that are spread by contact with the feces of an infected person, walking barefoot on contaminated soil, or consuming food containing the parasite’s eggs. Once inside the body, adult worms live in the intestines and produce thousands of eggs a day.

(2)A person with a moderate intestinal worm infection will have more than 200 worms in their body, each worm being between 8-12 inches, which could fill a three-liter jar.

(3) In 1910, John D. Rockefeller donated $1 million (the equivalent of $26 million dollars in 2019) to establish the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease (RSC) in the southern states of the United States.

(4) Treating kids for intestinal worms has a meaningful effect on their ability to learn. Studies show that deworming children actually leads to less absenteeism. For girls in particular, deworming increases their chances of graduating secondary school. And over time, children who are dewormed earn more money than their peers who are not.

(5) The primary way to treat kids for intestinal worms is through “school-based deworming campaign” – in which school-age children receive medicine at school. Schools make it easier to treat because children are already there and their teachers can easily be trained to distribute the medicine. In fact, the system has become so efficient that we can provide treatment for less than 25 cents per student per year in certain countries.

(6) The life cycle of all three types of intestinal worms include a pulmonary stage where the larvae are in the lungs of their human host and they move up the bronchial tubes. Then, they are coughed up and then swallowed – they eventually end up in the intestines where they mate and produce eggs.

(7) And finally, roundworms were found in fossilized feces from Peru dating back to 2277 B.C.

Intestinal worm infections prevent economic development in rural communities. They thrive in areas that lack access to sanitation and hygiene infrastructure. Children are especially vulnerable to the effects of these infections, such as stunted growth and weakened immune systems. These health impacts can limit their ability to attend school and learn effectively, which can diminish their earning potential as adults.

When these eggs hatch, intestinal worms cause abdominal pain, malnutrition, anemia, stunted growth, and impaired cognitive function. Children die every year from these intestinal parasites as a result of intestinal obstructions.

Deworming children can improve their health and transform the future of their communities. Treatment has a big impact for just a small investment – albendazole and mebendazole, the drugs used to treat intestinal worms, can be provided for less than fifty cents per person per year. Children who are dewormed miss less school and girls are more likely to graduate secondary school. As adults, they are able to earn more and support their families, which also leads to greater economic development for countries and regions.

With so many people requiring treatment for these intestinal parasites and the high prevalence rates in affected communities, the END Fund has partnered with local health workers and volunteers in Kenya, Rwanda, Ethiopia, and Zimbabwe to expand the outreach for mass drug administrations as part of the Deworming Innovation Fund.

Previously, mass treatments campaigns for intestinal worms in Kenya focused on children around 2 to 14 years old, but as part of this fund, the END Fund is expanding treatment to all high risk populations, helping to break the cycle of transmission.

Prevention strategies that focus on reducing the chance of transmission are another important part of controlling intestinal worms in humans, and have been extremely successful in Rwanda. These include:

- Precision mapping to find communities with high levels or risk in order to focus resources on these areas

- Combining deworming tactics with nutrition programming in order to reach pre-school age children

- Reaching pregnant women for deworming medication to help prevent anemia and other complications that can impact the health of the fetus

- The development of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene(WASH) programs to spread information about intestinal parasites and how to lower risk of contamination

In schools, these hygiene programs play an important part in educating communities on the importance of handwashing. Local public health advocates, volunteers, and teachers teach students about washing their hands after eating and after using the bathroom. This leads to a positive ripple effect, where children tell their families about the important of handwashing, and their families tell others in the community.

Key Facts

1 Billion

children require treatment worldwide1

20%

of the world’s population are at risk

100+

countries are endemic2

50¢

the cost to provide a person with annual treatment

Beyond the standard treatment: expanding to reach everyone at risk

NATIONAL DEWORMING DAYS HELP SCHOOL CHILDREN THRIVE

Sakshi is a class ten student at the Chief Minister Rise School in Barkhedi, a village in the central state of Madhya Pradesh, India. She remembers being sick as a child.

“When I was younger, I was often unwell. I used to ignore it and immediately after school instead ran to play with my friends. Our hands used to get dirty and we would eat food without washing our hands.”

In India, millions of children like Sakshi are at risk of intestinal worm infections. At this scale, the economic and development impacts of these infections can be enormous.

Every year on Madhya Pradesh’s annual National Deworming Day the students at Sakshi’s school receive a tablet called albendazole to treat intestinal worms. With these pills, generously donated by GSK, and the commitment and leadership from the Indian government and local institutions, the elimination of intestinal worm infections as a public health problem is on the horizon. The deworming program has resulted in the rate of children with intestinal worms dropping from over 12% in 2014 to 3.3% in 2019.

Pawan Karoch, headmaster of the region’s middle school division, knows firsthand the impact the National Deworming Day programming has had.

“I see visible results in the attentiveness and efficiency of my students—they are now healthier than before and can concentrate.” After taking albendazole, Sakshi’s stomach aches disappeared, and she now shares the importance of health and hygiene with her classmates.

The END Fund’s role in Stopping Parasitic infections

The END Fund is accelerating progress towards elimination of intestinal worms as a public health problem. Through the Flagship Fund, the END Fund supported 12 countries in 2023 to provide mass deworming treatment, reducing the prevalence and enabling children to live healthier lives. Its goal is to ensure no one is left behind.

To go even further, the Deworming Innovation Fund supports an additional four countries – Ethiopia, Rwanda, Zimbabwe, and Kenya – to prove that it is possible to stop the spread of intestinal worms by going beyond the standard approach of mass treatment campaigns. The Deworming Innovation Fund uses precision mapping, expanded treatments and improved water, hygiene and sanitation infrastructure to achieve its goals.

Other neglected tropical diseases